To understand black knot, a common fungal disease that affects plants, it’s helpful to understand the nature of diseases. A disease is a condition that harms the health of a living organism, be it a plant, human or animal. Diseases can be non-infectious (like nutrient deficiencies) or infectious, as in the case with black knot.

Most infectious plant diseases are caused by parasitic fungi that feed and grow on their plant hosts. As they do this, the plant becomes sick and, in some instances, dies.

Black knot is caused by the fungus Apiosporina morbosa, which naturally occurs throughout Canada and the United States. It thrives in moist climates where it’s host plants grows. Despite being widespread, the fungus only targets trees and shrubs from the Prunus genus. The most impacted species of this genus are ornamental, edible and native plums and cherries; however, apricots, peaches and almonds may also be affected.

How does black knot develop and spread?

Plant diseases have a disease cycle and understanding this cycle is key to managing and stopping its spread.

In the spring, spores (reproductive fungal cells) of the black knot fungus are released by rain. These spores travel by wind until they land on a wound or a susceptible young branch of a Prunus species. Once there, they germinate and begin growing between plant cells. Because growth begins inside a branch, symptoms of the infection usually go unnoticed for several months. However, this incognito growth soon ends.

As the fungus grows, it releases chemicals that trigger the plant to produce extra cells. This overproduction of cells results in the formation of swollen, woody, tumour-like growths along the outside of the infected branch. These growths, called galls or knots, are made up of both plant and fungal tissues. Younger galls are olive-green and velvety but eventually turn hard and black, giving the disease its common name.

It takes two years from the initial infection for the gall to harden and blacken. At this point, it is ready to release spores. Black galls overwinter and release spores in the wet spring, reinfecting the same plant host or finding a new plant host, repeating the cycle.

Susceptibility to black knot infection varies by Prunus species. For example, Canadian plum (Prunus nigra) and chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) are highly susceptible to black knot infection and damage, while others like pin cherry (Prunus pensylvanica) are susceptible to infection but can better tolerate the disease, resulting in less damage.

How does black knot damage trees?

The damage caused by black knot depends on the plant species and the scale of infection.

Black knot disfigures the trees and shrubs it infects. Multiple galls on a tree are considered unattractive and can lead to misshapen or stunted branches that impact the aesthetic form.

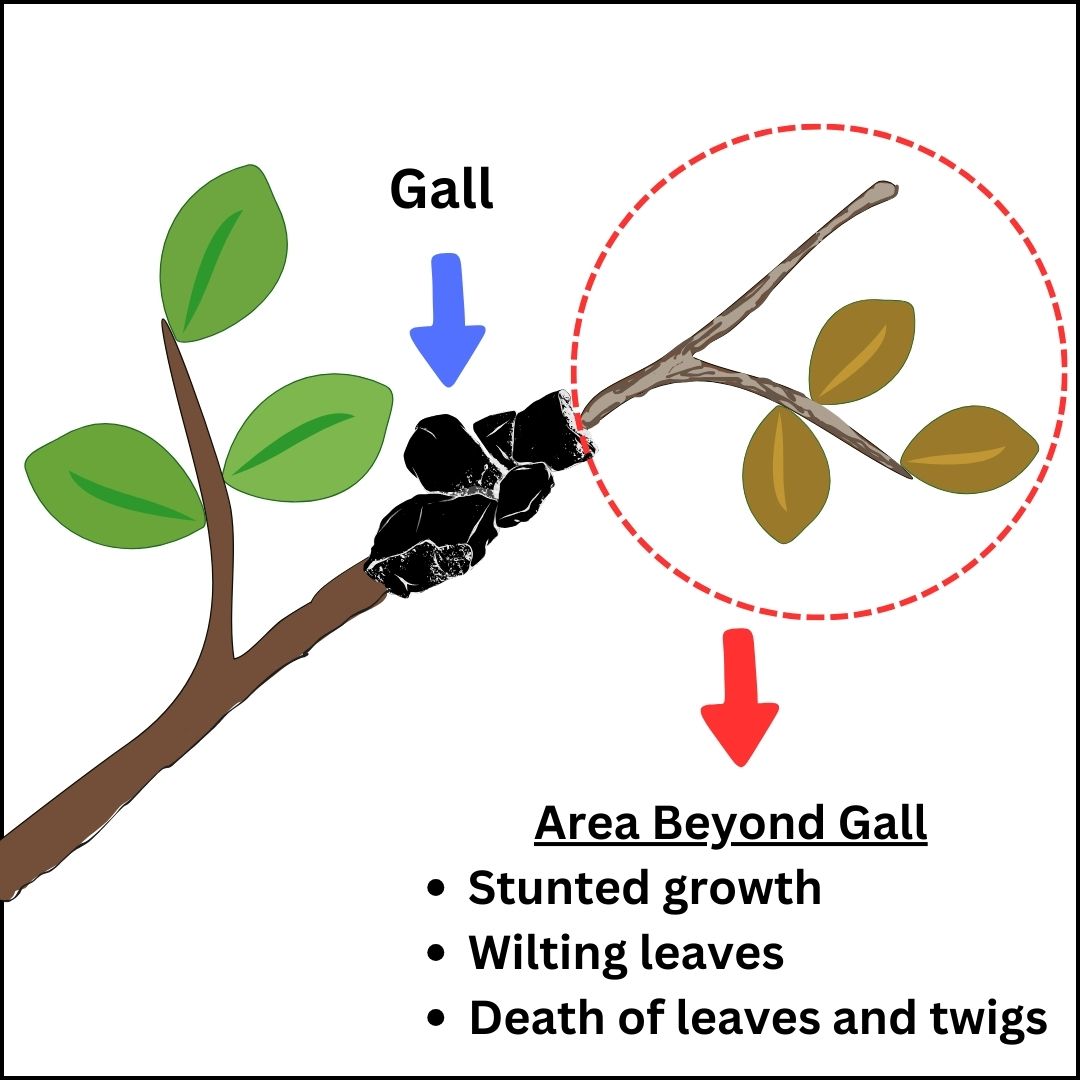

The disease can also have serious health impacts. As black knot galls grow, they can interrupt the flow of essential resources in the infected branch, leading to wilted leaves and stunted growth in the area beyond the infection site. If a gall grows big enough, it can encircle a branch, cutting off resources completely, leading to dieback. If a plant is infected with many galls, the stress can make it susceptible to other threats. In some cases, highly infected plants may die.

How to manage black knot disease

- Identify and monitor – Learn to recognize Prunus species and regularly monitor them for signs of black knot. Early identification is key to reducing spread. Galls are most noticeable during the winter months after leaf drop.

- Proactive planting – Avoid planting Prunus species near already infected plants. When possible, choose Prunus species with better tolerance to black knot.

- Prune affected branches – Remove branches with visible galls before spring, ideally in late fall or late winter when temperatures are below freezing. Hire an ISA certified arborist to ensure proper pruning and sanitization.

- Destroy diseased wood – Galls must be destroyed immediately after removal as they can continue to release spores. Burn the diseased wood onsite or place them in a sealed plastic bag and put them in the garbage.

- Foster health – Boost the resilience of your Prunus species by providing regular care to help reduce the impact of disease should infection occur.

- Fungicides – in certain instances, fungicides may help prevent infection in young, at-risk Prunus species. Speak with an ISA certified arborist to determine if this treatment is appropriate.

Don’t be afraid of the big black knot! When it comes to this disease, knowledge is power. Monitoring and early identification coupled with proper pruning techniques are effective at stopping the spread of this disease before it gets out of hand.

Jess Wilkin is the Residential Planting Programs Operations Supervisor and an ISA certified arborist at LEAF.

LEAF offers a subsidized Backyard Tree Planting Program for private property. The program is supported by the City of Toronto, the Regional Municipality of York, the City of Markham, the Town of Newmarket, the City of Vaughan, the Regional Municipality of Durham, the Town of Ajax, the Municipality of Clarington, the City of Oshawa, the City of Pickering, the Township of Scugog and the Town of Whitby.