I am enrolled in the University of Toronto's Forest Conservation undergraduate program (the lesser- known sibling of the Master of Forest Conservation program) with a focus on science and a minor in Geographical Information Systems (GIS). As a child, I spent a lot of time in nature. My family was fortunate enough to have a cottage where I learned, through experience, what a less human-centered environment feels like. Every time I'm lucky enough to get up there, I approach the trees, rocks, mushrooms, and mosses with even more understanding and appreciation.

My studies at U of T have been extremely broad. I've learned to think on an ecosystem level and it has permanently changed the way I view the urban landscape. Even the way that we direct water through our urban environment is quite different than the way that it would move through a functioning ecosystem, which recycles its own waste and replenishes its own supplies. Micro-organisms (tiny critters) break down complex chains of molecules by chewing dead matter and excreting it as available nutrients. Plants take up these nutrients in their roots and grow, providing food and oxygen for herbivores, and so the cycle continues when these animals die.

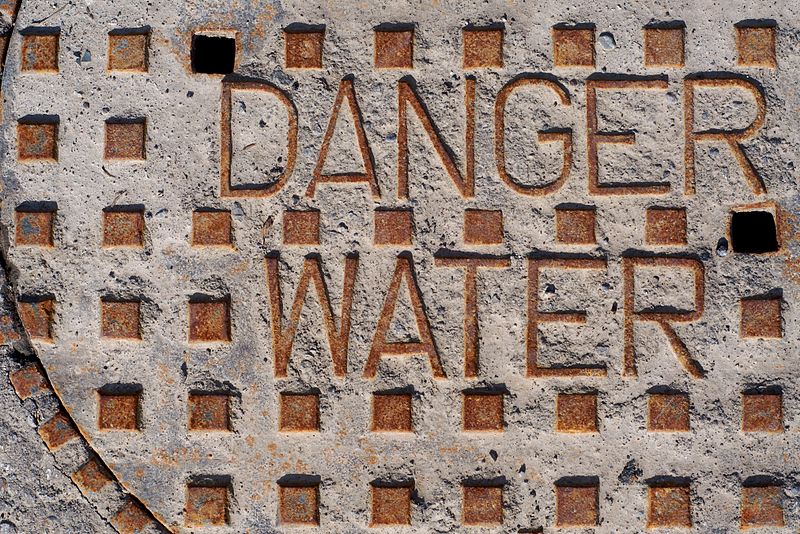

It can get more complex than this, but even in a simple example it is easy to see how human infrastructure interferes with the balance of that cycle. We compact our urban soil in an attempt to stabilize our foundations and to keep our bridges and roads from crumbling and cracking, but rainwater cannot percolate through the compacted soil and must be diverted through other means, for instance via a complex sewer system infrastructure.

Biologist George W. Koch describes the way, in a more naturally functioning ecosystem, water percolates through the soil, gets picked up by tree roots, and is transported back up through the drinking-straw-like "xylem" in its trunk. The leaves use some of the water for photosynthesis and release the leftover water back into the air. This provides cool shade and a moist environment in the direct vicinity of the tree. Water that is not picked up by trees and smaller vegetation percolates through the soil, recharging our groundwater and streams.

This would happen in Toronto, but compacted soil prevents rainwater from percolating through to the groundwater, and most of our streams were buried during settlement and turned into sewers.

In our urban environment, rainwater and snow melt flow along concrete paths, picking up dirt, grease, salt, and other pollutants along the way. This runoff flows into the sewer grates and flows directly into the lake, which is a concern that the City of Toronto addressed with their 2005/2006 public awareness campaign.

Older parts of the city have a combined sewer, where the pipes coming from houses connect to the storm water sewers (rather than separate sanitary sewers), adding water from sinks, toilets, and baths to the storm water mix. Typically, combined sewer water does undergo treatment before being returned to the lake, but during flood events these treatment centers exceed their capacity and the raw combined-sewer water overflows into Lake Ontario. This can cause populations of E. Coli to grow.

The city simply cannot handle the volume of water flowing across hard parking lots and streets, as Jessica Lemieux of Spacing points out. As more areas are compacted and paved for housing developments, even more runoff will occur. The City of Toronto is looking at how green infrastructure (trees, ponds, ditches) can help deal with our water waste and the Green Infrastructure Ontario Coalition is working to gain provincial support for more investment in green infrastructure. In a functioning ecological system, we would deal with our waste locally. I am looking at how trees can deal with rain where it falls so that we do not have to direct it through our already taxed sewers and into our precious freshwater lake.

People are sometimes incredulous at the thought of studying forestry in the middle of Toronto. The problem is that many of us do not realize our place in the urban forest ecosystem. Once we understand this, we can become responsible citizens and get involved in building healthy, sustainable cities. Of course, we’ll still enjoy going up to the cottage, but maybe we will enjoy coming home too.

Anna Mernieks is a senior undergraduate student at the University of Toronto specializing in Forest Conservation Science with a minor in GIS. Anna is also the songwriter for a band called Beams.