Mr. Voeten is formally known as a Master Arborist and Concept Manager at SHFT, but informally, he’s known as an inventor, scientist, engineer, drone-repair enthusiast, and, if you've seen him speak before, a stand-up comic.

What's striking about Mr. Voeten is his deep-rooted understanding of the irreplaceable role trees play in cities. He explained that Amsterdam sits on average 2.7 meters below sea level and its trees remove 900 million liters of groundwater each day during summer. “If the trees were to all die,” he had us imagine, “try finding an engineer who could build you a pump for this job.”

Urban forests offer an abundance of other benefits. They help prevent diabetes (which translates to healthcare savings), cool down our streets, increase property values, reduce heating and cooling costs, provide food for those in need, and the list goes on.

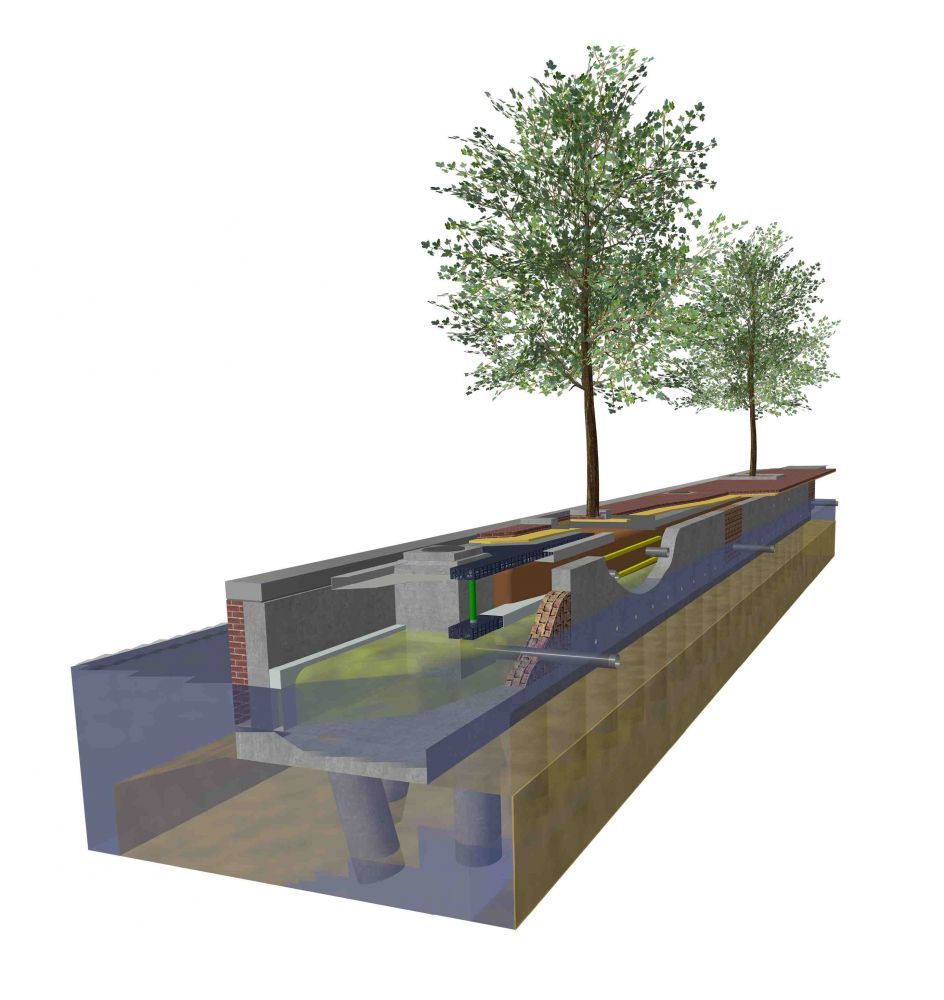

Mr. Voeten spends his time protecting Amsterdam's trees and does so with a special understanding of how they work. He designs tree pits with root-handles (or root-anchors). Roots will naturally wrap around these handles, which, he explains, helps prevent trees from blowing over in a storm. Mr. Voeten also told us that when roots uplift and damage sidewalks, it's because they're looking for oxygen. "You can't force tree roots to grow just anywhere you want, but you can entice them to grow where they do no damage." He solves this problem by designing tree pits with oxygen flow deep below the ground.

Cross section image of the complete tree growing site design for trees along the canals in Amsterdam. Image courtesy of Permavoid (www.permavoid.co.uk)

Mr. Voeten showed us how he solved two design challenges. At first, each problem seemed to me daunting and impossible. But as he showed us how he arrived at his solutions, I sensed that we could solve many of Toronto's arboreal problems if we approached them like Mr. Voeten ― stating the challenge clearly, thinking carefully, conducting attentive experiments, and making designs simple enough to be built with LEGO®.

A LEGO® model of the growing site construction. “If you can’t model your design with basic LEGO® bricks, it is probably still too complex”, says Mr. Voeten. Image courtesy of SHFT (www.shft.nl)

Strangely, Mr. Voeten spoke only about Amsterdam's urban forest and never mentioned Toronto's. During the coffee break, he told me that he didn't fly here to tell Toronto what to do; he came here to inspire us by showing what can be done. It was inspiring to see how Mr. Voeten approaches design challenges and devises elegant, effective, and long-lasting solutions.

Mr. Voeten pushes the limits of what we think can be done. He has designed a green roof that filters black-water (human waste) and turned lifeless, landfill-bound glass into fertile soil. He envisions a luscious city, flourishing with trees, dotted with livestock grazing on roofs, lined with living walls, and even cascading waterfalls. His fresh perspective inspired attendees to push new limits in Toronto and to grow the kind of urban forest a sustainable city needs.

Artist impression of future Amsterdam. Image courtesy of De Groene Grachten (www.degroengrachten.nl)

Jonathan Silver is a guest blogger and volunteer photographer for LEAF. He enjoys exploring built and natural places by foot, bike, ski, and canoe. Working as a wilderness guide, he developed a passion for nature. He now works towards solving environmental problems by closing the experiential gap between our actions and their effects ― an interest that started during his MA in Philosophy at the University of Toronto.